Ever since Supertyphoon “Yolanda” (Haiyan) hit the Philippines and our geothermal power plants in Leyte with such devastation in 2013, I have been of the view that new kinds of partnerships among public, private, community and research groups are needed to cope with the challenges yet to come from climate change. We cannot be certain of what’s coming as the past is no longer a reliable gauge for the future; but we all stand a greater chance against the angry forces of nature if we mount a concerted and cooperative effort to understand what’s going on and what we must do to prepare ourselves collectively.

Eye of the storm

To help us think about what we need to do to create a climate-resilient nation, allow me to share our story at Energy Development Corporation (EDC) as we literally had to live through the eye of many storms, including Haiyan, and adapt to climate realities today.

EDC is the largest renewable energy company in the country. Our plants and concession areas are spread out over 250,000 hectares throughout the country. Together they account for almost 1% of the country’s landmass.

Many of our energy facilities are located alongside lush beautiful watershed areas that are home to so many amazing flora and fauna that’s practically a showcase of our country’s biodiversity; one of the richest in the world. We consider this a huge responsibility and so, in partnership with the UP Institute of Biology (UPIB), we are studying the biodiversity around all our plants to better understand the ecosystem and how best to protect it; it also guides us on the proper way to reforest the more than 10,000 hectares with 6.5 million trees that has been ongoing since 2008.

In the process, we’ve come across many incredible living things within our concession areas like: the Philippine Eagle, Tarsiers (in Leyte and not just Bohol), the vulnerable Anas luzonica or Wild Philippine Duck, some species of Flying Foxes that were believed to be almost extinct, and an incredible mammal called the Flying Lemur that will remind you of the caped crusader.

Best-Smelling Rafflesia

Also, after almost two years of quiet study, recently, the UPIB team announced the discovery of a new species of Rafflesia named Rafflesia consueloae, now officially the world’s smallest and best smelling of what many consider the largest and “stinkiest” flower in the world. This was discovered around our hydro plant in Pantabangan, Nueva Ecija as part of the biodiversity inventory work we support.

However, over the years of working in these areas, we noticed a disturbing pattern emerging. The last 15 years, our geothermal energy facilities have shown damage from extreme weather events totaling P9 billion; but more than 85% of this number was incurred only in the last 5 years. With this, our insurance premiums have been climbing from just P243 million in 2011 to P682 million in 2015 (an increase of 180%, and could reach P1 billion this year based on initial estimates). Insurers and investors are now beginning to see extreme weather events as an everyday risk.

Then in November 2013, Typhoon Haiyan hit. And much of what stood for the last 30 years was devastated by a force no one alive had ever experienced before. During Al Gore’s presentation, I was struck by his phrase: “All our infrastructure was built for a world that’s now changing”. As he said that, many old images of our Haiyan-damaged plants in Leyte began flooding my mind.

Lessons

But Haiyan also taught us many lessons:

We all have to make a heroic effort to continually understand the world that’s coming, what science predicts, and where we may each be vulnerable. As a businessman, I found it essential to engage with the scientific community so we can jointly make sense of what’s going on, demystify it, make the lessons more accessible to the general public so that policies as well as everyday decisions and actions are guided properly.

This was the reasoning behind the Oscar M. Lopez Center collaborating with the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) in publishing its “State of the Philippine Climate 2015”. EDC and the OML Center are also supporting some of the work being done locally by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) of the US and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) on what they’re calling the Total Carbon Column Observation Network (TCCON for short). The latter is operating a network of monitoring stations around the world in an effort to understand atmospheric processes taking place globally today.

There’s a big gap in understanding what’s going on around the Philippines and the Pacific atmospherically, and this lack of information has limited global carbon cycle and weather prediction models. By hosting a station right in our Burgos Wind Farm, we are helping the best minds address pressing questions in the understanding of science that will someday help improve the accuracy of weather forecasting and climate modeling for everyone.

We are also employing many engineering solutions that will typhoon-proof our energy facilities to withstand the 300 kph winds of the future.

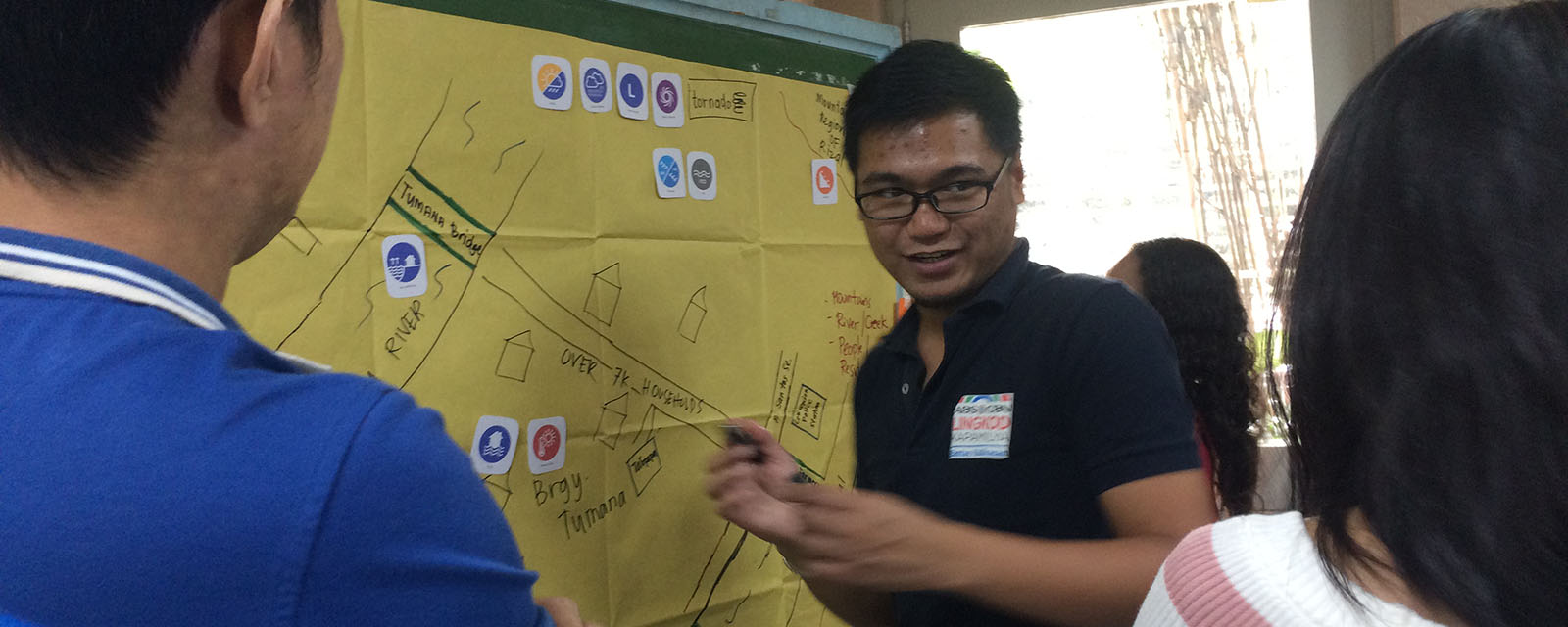

EDC has also employed a team of more than a dozen dedicated and well-equipped disaster response professionals that are currently dispersed at our various plants. They are constantly training our internal corps of volunteers as well as teaching local communities and government units to be force multipliers and first responders.

We also have close relationships with third party contractors who strategically position heavy equipment at our sites and can be mobilized quickly to clear and repair roads after storms. This proved vital for mobilizing relief goods and medical supplies immediately after Haiyan and other storms. Our sites today also stockpile fuel, food, water, and communications equipment, which will enable our people to function even under extreme emergencies.

Collaboration

One of the most important lessons learned was that our ability to network and collaborate with others spelled the difference between life and death for so many.

Among companies in the Philippines, we must build an instinctive ability to rely on each other, know each other’s capabilities, who’s doing what and where. During Haiyan, we worked closely with our sister company TV network ABS-CBN that had relief goods and supplies bottlenecked at warehouses and ports.

EDC leased barges and even private aircraft that transported gensets, fuel, relief goods and medical supplies directly from Manila to alternative unused landing sites in Leyte, de-clogging supply chains to needy areas. That effort would ultimately mobilize 10.7 million meals to more than a million affected lives in the weeks immediately after Haiyan. Today, we are institutionalizing that instinct through the Philippine Disaster Resilience Foundation (PDRF), formed by the country’s largest business conglomerates.

Local government units in affected areas will always need help from outside parties. Yet people and communities cannot afford to see their LGUs incapacitated and paralyzed; otherwise, chaos and panic ensues. It’s critical during the first three days after disaster hits that the public sees them literally with the lights on and in control.

In coordination with the Mayor and Vice Mayor of Ormoc City in Leyte and their city council, we brought in fuel and gensets to power the municipal hall, hospital and community water supply within a few days just to restore a feeling of normalcy. Thus, the situation in Ormoc did not degenerate into looting and desperation as it did elsewhere.

Critical Days

Bringing resources during the first three to five days after a disaster are absolutely critical. Usually, however, LGUs will not have the resources to do this alone. National government can act but there will always be gaps, especially when time is of the essence.

This is where private companies can come in to bridge. Better yet if we have formalized venues between national government and the private sector to again develop an instinct to collaborate.

Efforts in this regard are being initiated by the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) under the Office of Civil Defense (OCD), PDRF, Manila Observatory, and various departments of government in an effort to build automatic muscle memory in this direction too.

Even in the rebuilding of schools, private sector harnessed the best architects to design schoolhouses that could withstand 250 kph winds based on Education department specifications and supervised the procurement and construction process. Sometimes, this helped keep the confidence of donors that money is being used judiciously.

For a technical vocational school that we operate for the local community in Leyte, we temporarily reoriented their curriculum from an 11-month one which graduated only 145 people in a year to a shorter three-month program which graduated some 830 during the same period, with carpentry and masonry certifications that allowed many from affected families to acquire skills and participate in the massive rebuilding of these communities in the island of Leyte.

Adaptation to climate realities is undoubtedly not a one-time event as the new normal is still evolving. It will take years, maybe decades. But all the attitudes and learning we take should form a positive feedback loop that will just get better over time. If successful adaptation is to happen, we will need mechanisms and institutions that help catalyze action, knowledge exchange, and collaboration among players amidst a changing planet.

No one has all the answers and we need to help each other as we make our way through the fog of climate change. Hopefully, what EDC learned literally being in the eye of the storm will spark ideas in others too, and we’re more than happy to share those lessons and learn from everyone else’s as we build a more resilient Asean together.